March 17, 2015

By 19 Japanese Historians

PREFACE

On February 11, 2015, Sankei Newspaper reported that last November and December, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (“MOFA”) requested to McGraw-Hill and Prof. Ziegler of University of Hawaii who is the author of an article relating to comfort women in the world history textbook for American high schools published by McGraw-Hill, to correct inaccurate expressions in the book. The Daily Toa (Korea) and the Washington Post also reported the similar write-up on February 7th and February 10th respectively in their newspapers.

After an annual general meeting of the American Historical Association took place on January 2nd, 19 historians led by Prof. Alexis Dudden of the University of Connecticut made a joint statement to protect the publisher and the author from “censorship” by the Japanese government, and the statement, entitled as “Standing with Historians of Japan” represented by Prof. Yoshimi Yoshiaki, was published in the monthly journal of Perspectives on History issued on March 2nd. (Refer to Attachment 1)

While we were not informed of the content of the request made by the MOFA, we studied the article on “Comfort Women” in page 853 of Version Five McGraw-Hill textbook, Traditions and Encounters, and we found many inappropriate expressions. Among other things, by focusing on the following eight points from (1) to (8) which were factual errors, we advise McGraw-Hill to correct them spontaneously.

TEXT

The article relating to Comfort Women in the textbook published by McGraw-Hill and the book reference are quoted below. The points (1) to (8) are underlined as inaccurate expressions in the quoted article.

J.H. Bentley and Herbert F. Ziegler, Traditions & Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past, McGraw-Hill, 2011, p.853.

Comfort Women Women's experiences in war were not always ennobling or empowering. The Japanese army (1) forcibly recruited, conscripted, and dragooned (2) as many as two hundred thousand women (3) age fourteen to twenty to serve in military brothels, called "comfort houses" or "consolation centers". The army presented the women to the troops (4) as a gift from the emperor, and the women came from Japanese colonies such as Korea, Taiwan, and Manchuria and from occupied territories in the Philippines and elsewhere in sutheast Asia. The (5) majority of the women came from Korea and China.

Once forced into this imperial prostitution service, the "comfort women" catered to (6) between twenty and thirty men each day. Stationed in war zones, the women often confronted (7) the same risks as soldiers, and many became casualties of war. Others were killed by Japanese soldiers, especially if they tried to escape or contracted venereal diseases. At the end of the war, soldiers (8) massacred large numbers of comfort women to cover up the operation. The impetus behind the establishment of comfort houses for Japanese soldiers came from the horrors of Nanjing, where the mass rape of Chinese women had taken place. In trying to avoid such atrocities, the Japanese army created another horror of war. Comfort women who survived the war experienced deep shame and hid their past or faced shunning by their families. They found little comfort or peace after the war.

COMMENT

(1) forcibly recruited, conscripted: The group of 19 historians made a statement where only the real name of Yoshimi Yoshiaki was quoted. He wrote in his book, “Cases of women being deceived and led off are much more common among those rounded up in Korea”. (Yoshimi Yoshiaki, Comfort Women, p.103, Columbia University Press, 2000)

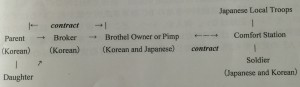

Yoshimi said in a discussion broadcast on TV in Japan that there was no evidence of forced recruitments in Korea. When comfort women were recruited in the Korean Peninsula, many people involved in recruiting were Koreans, and the relations between those who were involved can be explained in the following diagram.

Click to enlarge

(2) as many as two hundred thousand women: This figure is too large. Hata Ikuhiko estimates it to be around 20,000 as is shown in (5) below. Yoshimi wrote “at least around 50,000” (Rekishi-gaku kenkyuu, No. 849, 2008, p.4). Also refer to the comment on (6)

(3) age fourteen to twenty: According to the research cards of 20 comfort women (11 Japanese, 6 Koreans, 3 Taiwanese) who were captured by the US Forces in the Philippines in 1945, 19 persons were over 20 years old. (US National Archives, RG 389-PMG) The word “twenty”, therefore, should be corrected to “twenties”.

(4) as a gift from the emperor: This is too impolite expression for a school textbook, which defames the national head.

(5) majority of the women came from Korea and China: In Hata’s estimation, the total number of comfort women was around 20,000 in which Japanese amounted to around 8,000 as the single largest number, followed by Koreans amounting to around 4,000 half the Japanese. Chinese and others amounted to around 8,000.

(6) between twenty and thirty men each day: The numbers in 2) and 6) are greatly inflated, thereby self-contradicting. If (2) as many as two hundred thousand women had catered to (6) between twenty and thirty men each day, Japanese soldiers could have had sexual intercourses with them 4 million to 6 million times a day. The number of Japanese army men abroad was around 1 million in 1943. According to the textbook, all of them could have visited the comfort stations 4 to 6 times a day, meaning they had neither enough time to be engaged in combat nor for daily life activities.

(7) the same risks as soldiers: Comfort women and nurses worked in rear and relatively safe places which were distant from the front lines. The Japanese Army could not afford to allocate soldiers to guard comfort women in the front lines.

(8) massacred large numbers of comfort women: Is there evidence to prove that it happened? If the massacres of comfort women had occurred, the Tokyo Tribunals or BC class trials could have argued such an incident. However, there is no record. Without evidence of what, where and when on such statement, any textbook should not write it. Hata estimated that the death rate of comfort women was almost same as the one of the nurses (26,295 person) of the Japanese Red Cross Society. (Comfort Women and Battle Zone Sex, p.406, Shincho-sha, 1999)

19 Japanese Historians:

HATA, Ikuhiko 秦 郁彦 Nippon University

*

AKASHI, Yohji 明石 陽至 Nanzan University

ASADA, Sadao 麻田 貞雄 Dohshisha University

CHUNG, Daekyun 鄭 大均 Tokyo Metropolitan University

FUJIOKA, Nobukatsu 藤岡 信勝 Takushoku University

FURUTA, Hiroshi 古田 博司 University of Tsukuba

HASEGAWA, Michiko 長谷川 三千子 Saitama University

HAGA, Tohru 芳賀 徹 The University of Tokyo

HIRAKAWA, Sukehiro 平川 祐弘 The University of Tokyo

MOMOCHI, Akira 百地 章 Nippon University

NAKANISHI, Terumasa 中西 輝政 Kyoto University

NISHIOKA, Tsutomu 西岡 力 Tokyo Christian University

OH, Sonfa 呉 善花 Takushoku University

OHARA, Yasuo 大原 康男 Kokugakuin University

SAKAI, Nobuhiko 酒井 信彦 The University of Tokyo

SHIMADA, Yohichi 島田 洋一 Fukui Prefectural University

TAKAHASHI, Hisashi 高橋 久志 Sophia University

TAKAHASHI, Shiroh 高橋 史朗 Meisei University

YAMASHITA, Eiji 山下 英次 Ohsaka-City University

(In alphabetical order)

Attachment1

Standing with Historians of Japan

Alexis Dudden, March 2015

To the Editor:

As historians, we express our dismay at recent attempts by the Japanese government to suppress statements in history textbooks both in Japan and elsewhere about the euphemistically named “comfort women” who suffered under a brutal system of sexual exploitation in the service of the Japanese imperial army during World War II.

Historians continue to debate whether the numbers of women exploited were in the tens of thousands or the hundreds of thousands and what precise role the military played in their procurement. Yet the careful research of historian Yoshimi Yoshiaki in Japanese government archives and the testimonials of survivors throughout Asia have rendered beyond dispute the essential features of a system that amounted to state-sponsored sexual slavery. Many of the women were conscripted against their will and taken to stations at the front where they had no freedom of movement. Survivors have described being raped by officers and beaten for attempting to escape.

As part of its effort to promote patriotic education, the present administration of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe is vocally questioning the established history of the comfort women and seeking to eliminate references to them in school textbooks. Some conservative Japanese politicians have deployed legalistic arguments in order to deny state responsibility, while others have slandered the survivors. Right-wing extremists threaten and intimidate journalists and scholars involved in documenting the system and the stories of its victims.

We recognize that the Japanese government is not alone in seeking to narrate history in its own interest. In the United States, state and local boards of education have sought to rewrite school textbooks to obscure accounts of African American slavery or to eliminate “unpatriotic” references to the Vietnam War, for example. In 2014, Russia passed a law criminalizing dissemination of what the government deems false information about Soviet activities during World War II. This year, on the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide, a Turkish citizen can be sent to jail for asserting that the government bears responsibility. The Japanese government, however, is now directly targeting the work of historians both at home and abroad.

On November 7, 2014, Japan’s Foreign Ministry instructed its New York Consulate General to ask McGraw-Hill publishers to correct the depiction of the comfort women in its world history textbook Traditions and Encounters: A Global Perspective on the Past, coauthored by historians Herbert Ziegler and Jerry Bentley.

On January 15, 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported a meeting that took place last December between Japanese diplomats and McGraw-Hill representatives. The publisher refused the Japanese government’s request for erasure of two paragraphs, stating that scholars had established the historical facts about the comfort women.

On January 29, 2015, the New York Times further reported that Prime Minister Abe directly targeted the textbook during a parliamentary session, stating that he “was shocked” to learn that his government had “failed to correct the things [it] should have.”

We support the publisher and agree with author Herbert Ziegler that no government should have the right to censor history. We stand with the many historians in Japan and elsewhere who have worked to bring to light the facts about this and other atrocities of World War II.

We practice and produce history to learn from the past. We therefore oppose the efforts of states or special interests to pressure publishers or historians to alter the results of their research for political purposes.

Jeremy Adelman Princeton University

Jelani Cobb University of Connecticut

Alexis Dudden University of Connecticut

Sabine Frühstück University of California, Santa Barbara

Sheldon Garon Princeton University

Carol Gluck Columbia University

Andrew Gordon Harvard University

Mark Healey University of Connecticut

Miriam Kingsberg University of Colorado

Nikolay Koposov Georgia Institute of Technology

Peter Kuznick American University

Patrick Manning University of Pittsburgh

Devin Pendas Boston College

Mark Selden Cornell University

Franziska Seraphim Boston College

Stefan Tanaka University of California, San Diego

Julia Adeney Thomas Notre Dame University

Jeffrey Wasserstrom University of California, Irvine

Theodore Jun Yoo University of Hawaii

Herbert Ziegler University of Hawaii

Editor’s Note: This letter originated from an informal meeting held at the AHA annual meeting on January 2, 2015 in New York City.

Attachment 2

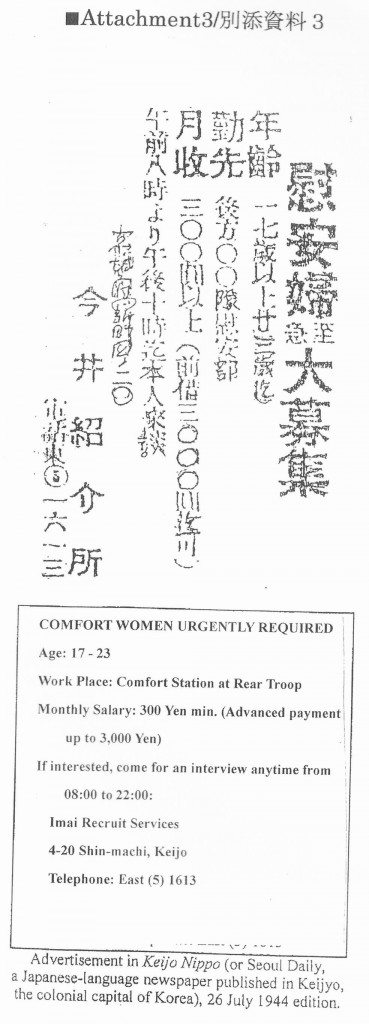

UNITED STATES

OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION

Psychological Warfare Team

Attached to U.S. Army Forces

India-Burma Theater

APO 689

| Japanese Prisoner of War Interrogation Report No. 49. | Place interrogated: Ledo Stockade Date Interrogated: Aug. 20 - Sept. 10, 1944 Date of Report: October 1, 1944 By: T/3 Alex Yorichi |

| Prisoners: 20 Korean Comfort Girls Date of Capture: August 10, 1944 Date of Arrival: August 15, 1944 at Stockade |

PREFACE

This report is based on the information obtained from the interrogation of twenty Korean "comfort girls" and two Japanese civilians captured around the tenth of August, 1944 in the mopping up operations after the fall of Myitkyin a in Burma.

The report shows how the Japanese recruited these Korean "comfort girls", the conditions under which they lived and worked, their relations with and reaction to the Japanese soldier, and their understanding of the military situation.

A "comfort girl" is nothing more than a prostitute or "professional camp follower" attached to the Japanese Army for the benefit of the soldiers. The word "comfort girl" is peculiar to the Japanese. Other reports show the "comfort girls" have been found wherever it was necessary for the Japanese Army to fight. This report however deals only with the Korean "comfort girls" recruited by the Japanese and attached to their Army in Burma. The Japanese are reported to have shipped some 703 of these girls to Burma in 1942.

RECRUITING;

Early in May of 1942 Japanese agents arrived in Korea for the purpose of enlisting Korean girls for "comfort service" in newly conquered Japanese territories in Southeast Asia. The nature of this "service" was not specified but it was assumed to be work connected with visiting the wounded in hospitals, rolling bandages, and generally making the soldiers happy. The inducement used by these agents was plenty of money, an opportunity to pay off the family debts, easy work, and the prospect of a new life in a new land, Singapore. On the basis of these false representations many girls enlisted for overseas duty and were rewarded with an advance of a few hundred yen.

The majority of the girls were ignorant and uneducated, although a few had been connected with "oldest profession on earth" before. The contract they signed bound them to Army regulations and to war for the "house master " for a period of from six months to a year depending on the family debt for which they were advanced ...

Approximately 800 of these girls were recruited in this manner and they landed with their Japanese "house master " at Rangoon around August 20th, 1942. They came in groups of from eight to twenty-two. From here they were distributed to various parts of Burma, usually to fair sized towns near Japanese Army camps. Eventually four of these units reached the Myitkyina. They were, Kyoei, Kinsui, Bakushinro, and Momoya. The Kyoei house was called the "Maruyama Club", but was changed when the girls reached Myitkyina as Col.Maruyama, commander of the garrison at Myitkyina, objected to the similarity to his name.

PERSONALITY;

The interrogations show the average Korean "comfort girl" to be about twenty-five years old, uneducated, childish, and selfish. She is not pretty either by Japanese of Caucasian standards. She is inclined to be egotistical and likes to talk about herself. Her attitude in front of strangers is quiet and demure, but she "knows the wiles of a woman." She claims to dislike her "profession" and would rather not talk either about it or her family. Because of the kind treatment she received as a prisoner from American soldiers at Myitkyina and Ledo, she feels that they are more emotional than Japanese soldiers. She is afraid of Chinese and Indian troops.

LIVING AND WORKING CONDITIONS;

In Myitkyina the girls were usually quartered in a large two story house (usually a school building) with a separate room for each girl. There each girl lived, slept, and transacted business. In Myitkina their food was prepared by and purchased from the "house master" as they received no regular ration from the Japanese Army. They lived in near-luxury in Burma in comparison to other places. This was especially true of their second year in Burma. They lived well because their food and material was not heavily rationed and they had plenty of money with which to purchase desired articles. They were able to buy cloth, shoes, cigarettes, and cosmetics to supplement the many gifts given to them by soldiers who had received "comfort bags" from home.

While in Burma they amused themselves by participating in sports events with both officers and men, and attended picnics, entertainments, and social dinners. They had a phonograph and in the towns they were allowed to go shopping.

PRIOR SYSTEM;

The conditions under which they transacted business were regulated by the Army, and in congested areas regulations were strictly enforced. The Army found it necessary in congested areas to install a system of prices, priorities, and schedules for the various units operating in a particular areas. According to interrogations the average system was as follows:

| 1. Soldiers | 10 AM to 5 PM | 1.50 yen | 20 to 30 minutes |

| 2. NCOs | 5 PM to 9 PM | 3.00 yen | 30 to 40 minutes |

| 3. Officers | 9 PM to 12 PM | 5.00 yen | 30 to 40 minutes |

These were average prices in Central Burma. Officers were allowed to stay overnight for twenty yen. In Myitkyina Col. Maruyama slashed the prices to almost one-half of the average price.

SCHEDULES;

The soldiers often complained about congestion in the houses. In many situations they were not served and had to leave as the army was very strict about overstaying. In order to overcome this problem the Army set aside certain days for certain units. Usually two men from the unit for the day were stationed at the house to identify soldiers. A roving MP was also on hand to keep order. Following is the schedule used by the "Kyoei" house for the various units of the 18th Division while at Naymyo.

| Sunday | 18th Div. Hdqs. Staff |

| Monday | Cavalry |

| Tuesday | Engineers |

| Wednesday | Day off and weekly physical exam. |

| Thursday | Medics |

| Friday | Mountain artillery |

| Saturday | Transport |

Officers were allowed to come seven nights a week. The girls complained that even with the schedule congestion was so great that they could not care for all guests, thus causing ill feeling among many of the soldiers.

Soldiers would come to the house, pay the price and get tickets of cardboard about two inches square with the prior on the left side and the name of the house on the other side. Each soldier's identity or rank was then established after which he "took his turn in line". The girls were allowed the prerogative of refusing a customer. This was often done if the person were too drunk.

PAY AND LIVING CONDITIONS;

The "house master" received fifty to sixty per cent of the girls' gross earnings depending on how much of a debt each girl had incurred when she signed her contract. This meant that in an average month a girl would gross about fifteen hundred yen. She turned over seven hundred and fifty to the "master". Many "masters" made life very difficult for the girls by charging them high prices for food and other articles.

In the latter part of 1943 the Army issued orders that certain girls who had paid their debt could return home. Some of the girls were thus allowed to return to Korea.

The interrogations further show that the health of these girls was good. They were well supplied with all types of contraceptives, and often soldiers would bring their own which had been supplied by the army. They were well trained in looking after both themselves and customers in the matter of hygiene. A regular Japanese Army doctor visited the houses once a week and any girl found diseased was given treatment, secluded, and eventually sent to a hospital. This same procedure was carried on within the ranks of the Army itself, but it is interesting to note that a soldier did not lose pay during the period he was confined.

REACTIONS TO JAPANESE SOLDIERS;

In their relations with the Japanese officers and men only two names of any consequence came out of interrogations. They were those of Col. Maruyama, commander of the garrison at Myitkyina and Maj. Gen.Mizukami, who brought in reinforcements. The two were exact opposites. The former was hard, selfish and repulsive with no consideration for his men; the latter a good, kind man and a fine soldier, with the utmost consideration for those who worked under him. The Colonel was a constant habitué of the houses while the General was never known to have visited them. With the fall of Myitkyina, Col. Maruyama supposedly deserted while Gen. Mizukami committed suicide because he could not evacuate the men.

SOLDIERS REACTIONS;

The average Japanese soldier is embarrassed about being seen in a "comfort house" according to one of the girls who said, "when the place is packed he is apt to be ashamed if he has to wait in line for his turn". However there were numerous instances of proposals of marriage and in certain cases marriages actually took place.

All the girls agreed that the worst officers and men who came to see them were those who were drunk and leaving for the front the following day. But all likewise agreed that even though very drunk the Japanese soldier never discussed military matters or secrets with them. Though the girls might start the conversation about some military matter the officer or enlisted man would not talk, but would in fact "scold us for discussing such un-lady like subjects. Even Col. Maruyama when drunk would never discuss such matters."

The soldiers would often express how much they enjoyed receiving magazines, letters and newspapers from home. They also mentioned the receipt of "comfort bags" filled with canned goods, magazines, soap, handkerchiefs, toothbrush, miniature doll, lipstick, and wooden clothes. The lipstick and cloths were feminine and the girls couldn't understand why the people at home were sending such articles. They speculated that the sender could only have had themselves or the "native girls".

MILITARY SITUATION;

"In the initial attack on Myitleyna and the airstrip about two hundred Japanese died in battle, leaving about two hundred to defend the town. Ammunition was very low.

"Col. Maruyama dispersed his men. During the following days the enemy were shooting haphazardly everywhere. It was a waste since they didn't seem to aim at any particular thing. The Japanese soldiers on the other hand had orders to fire one shot at a time and only when they were sure of a hit."

Before the enemy attacked on the west airstrip, soldiers stationed around Myitkyina were dispatched elsewhere, to storm the Allied attack in the North and West. About four hundred men were left behind, largely from the 114th Regiment. Evidently Col. Maruyama did not expect the town to be attacked. Later Maj. Gen. Mizukami of the 56th Division brought in reinforcements of more than two regiments but these were unable to hold the town.

It was the consensus among the girls that Allied bombings were intense and frightening and because of them they spent most of their last days in foxholes. One or two even carried on work there. The comfort houses were bombed and several of the girls were wounded and killed.

RETREAT AND CAPTURE;

The story of the retreat and final capture of the "comfort girls" is somewhat vague and confused in their own minds. From various reports it appears that the following occurred: on the night of July 31st a party of sixty three people including the "comfort girls" of three houses (Bakushinro was merged with Kinsui), families, and helpers, started across the Irrawaddy River in small boats. They eventually landed somewhere near Waingmaw, They stayed there until August 4th, but never entered Waingmaw. From there they followed in the path of a group of soldiers until August 7th when there was a skirmish with the enemy and the party split up. The girls were ordered to follow the soldiers after three-hour interval. They did this only to find themselves on the bank of a river with no sign of the soldiers or any mea ns of crossing. They remained in a nearby house until August 10th when they were captured by Kaahin soldiers led by an English officer. They were taken to Myitleyina and then to the Ledo stockade where the interrogation which form the basis of this report took place.

REQUESTS

None of the girls appeared to have heard the loudspeaker used at Myitkyina but very did overhear the soldiers mention a "radio broadcast."

They asked that leaflets telling of the capture of the "comfort girls" should not be used for it would endanger the lives of other girls if the Army knew of their capture. They did think it would be a good idea to utilize the fact of their capture in any droppings planned for Korea.

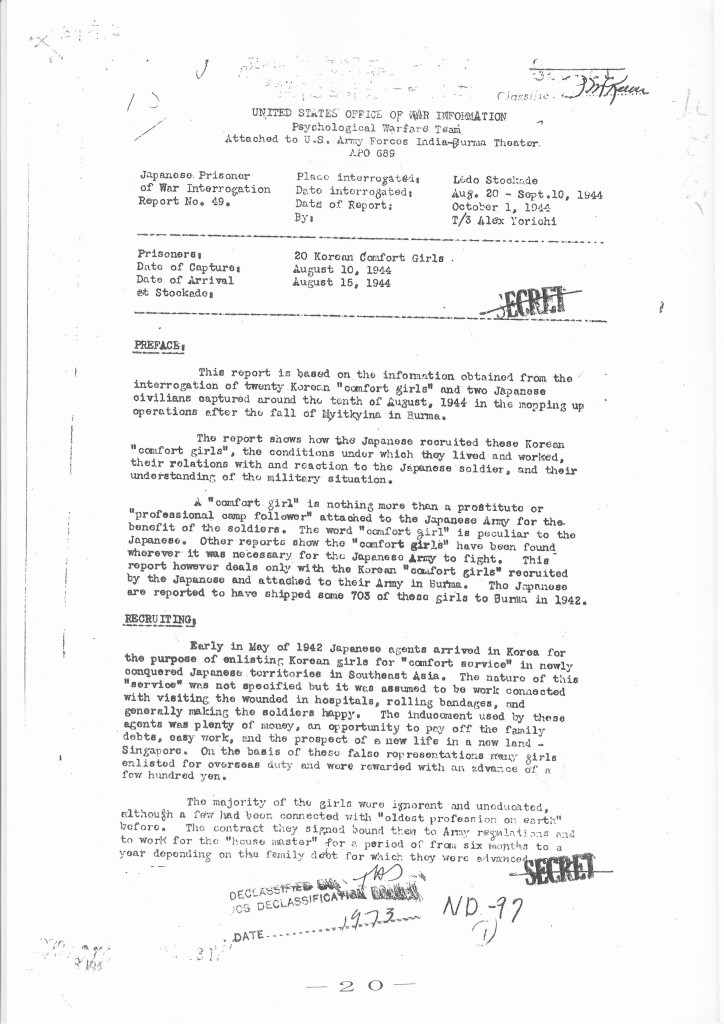

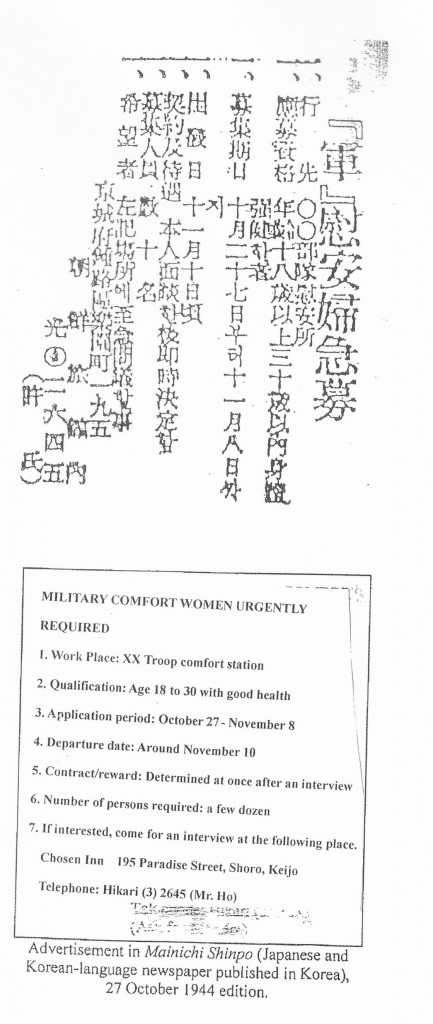

Attachment 3 Click to enlarge